Reviews

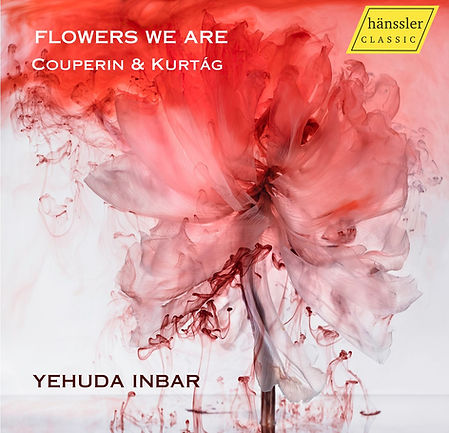

Album of the Week “Flowers we are” is the title of Israeli pianist Yehuda Inbar's new album. While studying François Couperin's complete harpsichord works, he made a surprising discovery: many of the compositional ideas in them are very similar to other pieces that Inbar already had in his repertoire – but these are almost 300 years younger. They are mostly very short piano compositions by the Hungarian György Kurtág. These mostly very short piano compositions by Kurtág are often ambiguous, explains the pianist: “The basic idea behind the titles of Couperin and Kurtág, when they write pieces about flowers or birds, for example, is that it's never just about describing things, but about something else. Namely, our existence or the human soul – and flowers are, of course, a beautiful metaphor for that.” Waltz with only one note An example of a very short yet tremendously energetic, dance-like piece by Kurtág is his “Prelude and Waltz,” which lasts less than a minute. "This is a piece based on only one note. Kurtág uses only C in different octaves and different lengths in the prelude, followed by a waltz. Very creative,“ says Yehuda Inbal. Finding counterparts was often detective work. Inbar discovered a short piece by Couperin, ”Tic-Toc Choc", which describes a very naturally minimal shift in rhythm, like a heartbeat or the clatter of hooves. “There is also repetition on the note C in this piece. A prelude from today, for something written 300 years ago.” Detective work There is something mathematical about Yehuda Inbar's playing, yet it does not sound calculated. Rather, it is like an alert interest in connections, puzzles, or clues that the composer has hidden in the notes. In fact, Yehuda Inbar studied not only music but also mathematics in his native Israel. In the original, François Couperin's pieces are all written for the harpsichord, with very precise playing instructions – although he allowed them to be played on other instruments such as the flute or strings. The composer even stipulated that the ornaments in particular should be performed exactly as he had painstakingly conceived them. Angelic music Yehuda Inbar interprets both the playing instructions for the concert grand piano and the titles of the works with great care and respect. “For example, ‘L'Angélique’. This can mean ‘the angel’, but Angélique is also French for lute. The piece is written in the deep register of the lute. In the second part of this piece, I transposed it two octaves higher, in dialogue with this Angélique title. Angélique, heavenly, celestial.” Eternal beauty The cover beautifully illustrates the timeless and weightless character of Yehuda Inbar's album: a photograph of a wilted flower, into which the artist Kathrin Linkersdorff has injected new color pigments, thus giving it eternal beauty. György Kurtág will turn 100 next year and is highlighted in a special way on this album. And François Couperin's 27 “Ordres” have long deserved to be viewed with today's eyes. Yehuda Inbar succeeds wonderfully in combining these two aspects. Julia Kaiser, radio3

Die neu Platte Couperin trifft Kurtag: Flowers we are By Elisabeth Richter

258 years of time and music history lie between François Couperin and György Kurtág. What do the French Baroque composer, born in 1668, and the contemporary Hungarian composer, born in 1926, have in common? One, Couperin, writes entirely tonal music, the other, Kurtág, writes free, non-tonal music; their rhythms, harmonies, and melodies differ. Pianist Yehuda Inbar has discovered similarities. Both Couperin and Kurtág often write very short pieces, miniatures with characteristic titles. They examine musical elements in particular detail, a rhythm, a dissonance, a melodic turn, or even just a single note. Playful elements and musical details In Kurtág's “Prelude and Waltz,” only the note “C” is heard—in different registers, thrown down like blots on a piece of paper. And then the waltz is clearly audible! Yehuda Inbar follows Kurtág's waltz with a piece by Couperin: it seems to imitate the ticking of clocks or the rhythmic hammering, beating, or trampling of horses. It has the imaginative title “Tic-Toc-Choc.” Couperin and Kurtág also have something playful about them. Kurtág's miniatures on this album are from his collection “Játékok,” which means “games.” Couperin was the most important harpsichordist of his time, among other things at the court of Versailles, with over 240 harpsichord works. He compiled them into “Ordres,” or suites. Yehuda Inbar selected several pieces from this collection for his album. In “Die verliebte Nachtigall” (The Nightingale in Love) by François Couperin, Yehuda Inbar conveys tenderness with a delicate and floating touch. Of course, this music was not originally written for a modern piano. But Couperin's harpsichord works were often played on other instruments even during his lifetime. In his very readable, detailed booklet text, Yehuda Inbar explains that his playing on a grand piano is nothing more than another arrangement. And when a pianist plays in such a nuanced, exciting, and colorful way, all concerns become insignificant. New perspectives on familiar works Different instruments and different sounds open up new and unfamiliar ways of listening to music. The contrast between Couperin and Kurtág also allows the pieces by both composers to be heard differently, more attentively. In György Kurtág's piece “Apple Blossom,” one can easily imagine the delicate buds sprouting, or completely different thoughts may come to mind. That is the appeal of this album: Couperin's and Kurtág's miniatures simply offer great freedom of perception; they invite calm and concentration, and amazement! This album is pure joy. Elisabeth Richter

Subtle and fantastic: Inbar plays Couperin and Kurtág Pianist Yehuda Inbar juxtaposes Couperin's Baroque music with contemporary works by Kurtág. Elisabeth Richter finds out whether it works. (Hänssler)

Album of the year & Album of the month on reviewers choices by Elisabeth Richter Flowers we are. Piano works by Couperin and Kurtág; Yehuda Inbar; Hänssler There are 258 years between the two composers. They write short pieces with characteristic titles, small portraits. Or they examine a musical element closely. Yehuda Inbar contrasts the two composers with subtle tonal differences, drawing attention to each other.

L'ACTUALITÉ DU DISQUE By Arnaud Merlin

Pizzicato, Luxemburg (4/5) With this program, Yehuda Inbar wants to show the connection between Couperin and Kurtág. And if some of the transitions work wonderfully, others reveal stronger breaks that make us realize that 200 years separate the two composers. Overall, this is a very poetic journey through the music of François Couperin and György Kurtág. Technically, there is no doubt about this performance. Inbar’s playing meets the requirements of both Couperin and Kurtag. Norbert Tischer

This new album from Israeli pianist Yehuda Inbar, released ahead of György Kurtág‘s 100th birthday in February 2026, brings together music written over 200 years apart – a selection of pieces from different Ordres by Couperin and from various books of Játékok (‘Games’) by Kurtág, which juxtaposed and intertwined, reveal unexpected musical and conceptual connections and reflections between the music of the both composers. This is not the first time Inbar has combined the contemporary and the past. His debut disc, an investigation of Schubert’s identity through the composer’s unfinished sonatas, included music by Michael Finnissy and Jörg Widmann. By bringing seemingly unrelated works together, Inbar creates intriguing programmes where new light is thrown on the old, and vice versa. The title of the album is taken from the final piece on the recording, and reflects how Couperin’s and Kurtág’s music is richly inspired by nature, portraying in sound flowers, birds, plants, light and shadow, the play of water, and more. Often imbued with symbolism, these depictions of nature serve as commentary on and allegories for the human soul and human existence. In addition, many of Couperin’s and Kurtág’s pieces are autobiographical portraits and homages to figures often in their personal lives. Kurtág dedicated many of his pieces to his wife and close musical collaborator, Márta; some to close friends, to mark occasions such as birthdays or farewells; as well as homages to other artists and composers, including Bach, Schubert, Webern and others. Like Kurtág , Couperin, one of the leading clavecinistes of his day, enjoyed paying tribute in his music to members of the French court, Mademoiselle de La Plante (a famous harpsichordist of the time) or his contemporary Jean-Baptiste Lully, amongst others. Kurtág’s Játékok, comprising short pieces, some only moments long, often idiosyncratic or aphoristic, provides the perfect foil for Couperin’s writing, and Yehuda Inbar has been careful to select pieces which contrast and complement one another. For example, Kurtág’s sparse Prelude & Waltz in C, lasting just over half a minute, with its repetition of the note of C, becomes the prelude to the repeated notes in Couperin’s Le Tic-Toc-Choc. Elsewhere, Kurtag’s pieces act like little palate cleansers, their piquancy or atonality contrasting with Couperin’s elegance and consonance. Overall, this is a most intriguing and enjoyable recording. Beautifully presented, Inbar makes an excellent case for playing music for harpsichord on the modern piano: his appreciation of the architecture of Couperin’s music is paired with supple phrasing, sensitive articulation, subtle dynamics and a glowing tone. He brings a delightful playfulness and wit to Kurtag’s miniatures.

From the Baroque era to the present day, it can be just a stone's throw. David Greilsammer, for example, played Scarlatti sonatas on the piano right next to John Cage and his experiments. His Israeli compatriot Yehuda Inbar, who lives in Berlin, achieves a similarly stimulating result by confronting character pieces by Louis Couperin with modern sound sketches by György Kurtág on “Flowers we are”: as if the music briefly withdraws into itself to reorganize itself, letting sounds fall like murmurs, and listen pensively to chords and overtones. This is an exciting contrast to Couperin's dreamlike, softly played baroque moments, such as the famous “Mysterious Barricades” – which at the time probably referred to the eyelashes of fine ladies. (hänssler) WOLF EBERSBERGER

Almost 360 years separate their birth years, and their countries of origin and personal histories also have little in common. And yet Israeli pianist Yehuda Inbar senses an inner connection between French Baroque composer François Couperin, born in 1668, and Hungarian György Kurtág, who will turn 100 next February. On the one hand, there is Couperin, one of the most important musicians in the Versailles milieu; on the other, there is György Kurtág, an emigrant who fled to the West before the Hungarian uprising in 1955 and went on to become one of the most important Hungarian composers of new music. Both were or are masters of miniatures, which they published in extensive collections. From several of Couperin's albums and Kurtág's compendium “Játékok” (Games), which comprises several hundred pieces, Yehuda Inbar selected 29 works and compiled them for his new album entitled “Flowers We Are.” As different as the musical languages of the Baroque master and his contemporary may be, Inbar sees a commonality not only in their preference for short, pointed aphorisms ranging from a few bars to a maximum of four minutes, but also in the peculiarity of understanding each miniature as a character piece dedicated to and modeled after specific people, animals, natural phenomena, or other events. In Couperin's case, these are musical profiles of the royal family, in Kurtág's case, memories of his wife and friends. But nightingales and steam hammers also make themselves heard. Inbar's interpretations reveal the joy with which he attempts to trace these subtle characterizations. This is particularly convincing in Kurtág's extremely short pieces, which he expresses with a spirited touch and crystalline clarity. In contrast to Couperin's denser but equally transparent sound textures, which Inbar performs on the modern grand piano in a rather soft, sometimes romanticized, dreamy manner, and which do not always exhibit the precise differentiation of his Kurtág interpretations.